“Before cookies, the web was essentially private. After cookies, the web becomes a space capable of extraordinary monitoring,” said Lawrence Lessig 20 years ago.

Approximately 83% of brands rely on third-party cookies. For the past couple of decades, cookies have been the leading source of tracking and monitoring internet users, allowing for sophisticated targeting, retargeting and personalization. With the impending demise of third-party cookies and recent restrictions on using mobile-device identifiers for ad targeting, marketers will need to overhaul their advertising strategies to prepare for a dramatically different landscape.

What’s coming:

- Starting in mid-2023, Google’s Chrome browser is expected to block 3rd Party cookies, which are already blocked in Safari and Firefox. Because Chrome is the leading browser —this cookie policy will effectively put an end to cookie-based advertising.

- Apple requires app providers to get permission from consumers before tracking them – and initial data suggests only 46 percent of consumers will agree, meaning app providers will be unable to track most users across the Apple ecosystem.

- Notably, both Google and Apple have said they will neither create nor support workarounds, such as probabilistic fingerprinting, to build user-level profiles in their ecosystems.

Make sure you have a plan.

In the short-term, the phasing out of cookies and device identifiers will have a negative effect on efficiency and ultimately ROI – but the good news is that there are new ways of targeting that advertisers can and should be testing before cookies disappear. There is no one-size-fits-all solution, but by creating a plan and assessing the various options, advertisers can set themselves up for the future.

- Assess your current use of cookies: Determine which cookies you are currently using on your website and which ones are critical for your advertising efforts.

- Evaluate alternative tracking methods: Explore other methods of tracking user behavior such as first-party data, contextual advertising, and server-side tracking.

- Build a first-party data strategy: Collecting first-party data directly from your audience can help you better understand their preferences and behavior and personalize their experiences.

- Develop a consent management plan: Be transparent with your audience about how you collect and use their data and provide them with options to manage their privacy settings.

- Test and optimize: Experiment with new approaches to tracking and targeting users, and optimize your strategies based on performance and user feedback.

Alternative tracking methods to evaluate and test.

Browser Based Tracking solutions use JavaScript code to track user behavior on a website and send that data to a server for analysis.

Device Based Tracking uses data from a user’s device, such as the IP address, to track their behavior across different websites.

Contextual Targeting is based on the content the user is viewing. While some may consider this a step back, new tools that use natural language processing and image recognition allow algorithms to grasp the sentiment of specific content with unprecedented speed and reliability, enabling marketers to display ads in an environment that is both highly relevant for their potential customers and safe for their brand.

Interest-based Targeting relies on data about a user’s website visits, but only to identify what broad content topics they’re interested in. Google’s Topics is one solution that learns about users’ interests as they surf the web and shares top interests with participating websites for advertising purposes, staying within a limited set of 350 broad topics and excluding sensitive topics like race or sexual orientation.

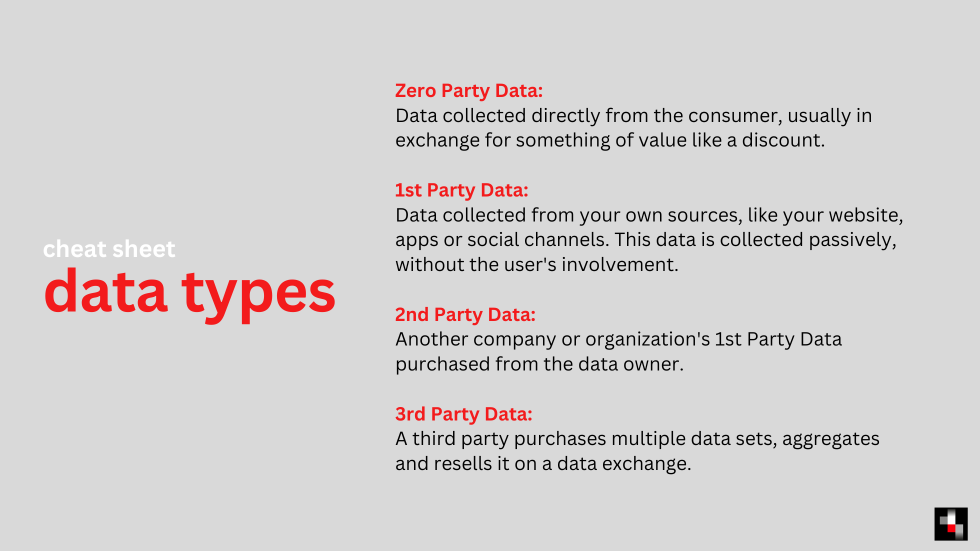

First-Party Data should continue to be priority (collecting data directly from owned channels, i.e., websites, apps) and should be supplemented with zero-party to understand preferences, intention, and lifestyle.

Second-Party Data Partnerships can help maximize the value of first-party data. Advertisers should seek partnerships to exchange data through a neutral third-party cloud solution. Targeting can then be done anonymously, allowing advertisers and media owners to expand relationships without violating regulations.

Universal IDs use hashed and encrypted email addresses from opted-in users as the basis for identity across devices – a significant advantage over cookies. These IDs are shared between publishers and advertisers to be used anonymously – and because the data is hashed and converted to a hexadecimal string, it does not violate regulations. Current partners offering Universal IDs are The Trade Desk, LiveRamp, Tapad, Neustar, Epsilon, Zeotap, Flashtalking, ID5 and LiveIntent.

It’s yet to be determined whether consent to use email addresses can be achieved at a large enough scale to meet the demand for advertising inventory. Collecting email will have a role in the post-cookie world, a significant one. However, it will coexist with other solutions, such as first-party data, opted-in GPS location tracking, and contextual (keyword) targeting.

The Net Net

While the phase-out of cookies may seem daunting, there are several alternative solutions available, and advertisers must be proactive about setting themselves us for the future. There isn’t one solution to replace cookies, it must be a combination of tactics to ensure you are using all available resources. It is also key to get ahead of the game rather than waiting until cookies are obsolete.