Street-Art: The Art of Change

Street art has revolutionised the art scene, redesigned the face of countless cities and triggered both large and small-scale changes around the globe. No art form is better representative of our topic “Change”, the overall theme running through this edition of TWELVE.

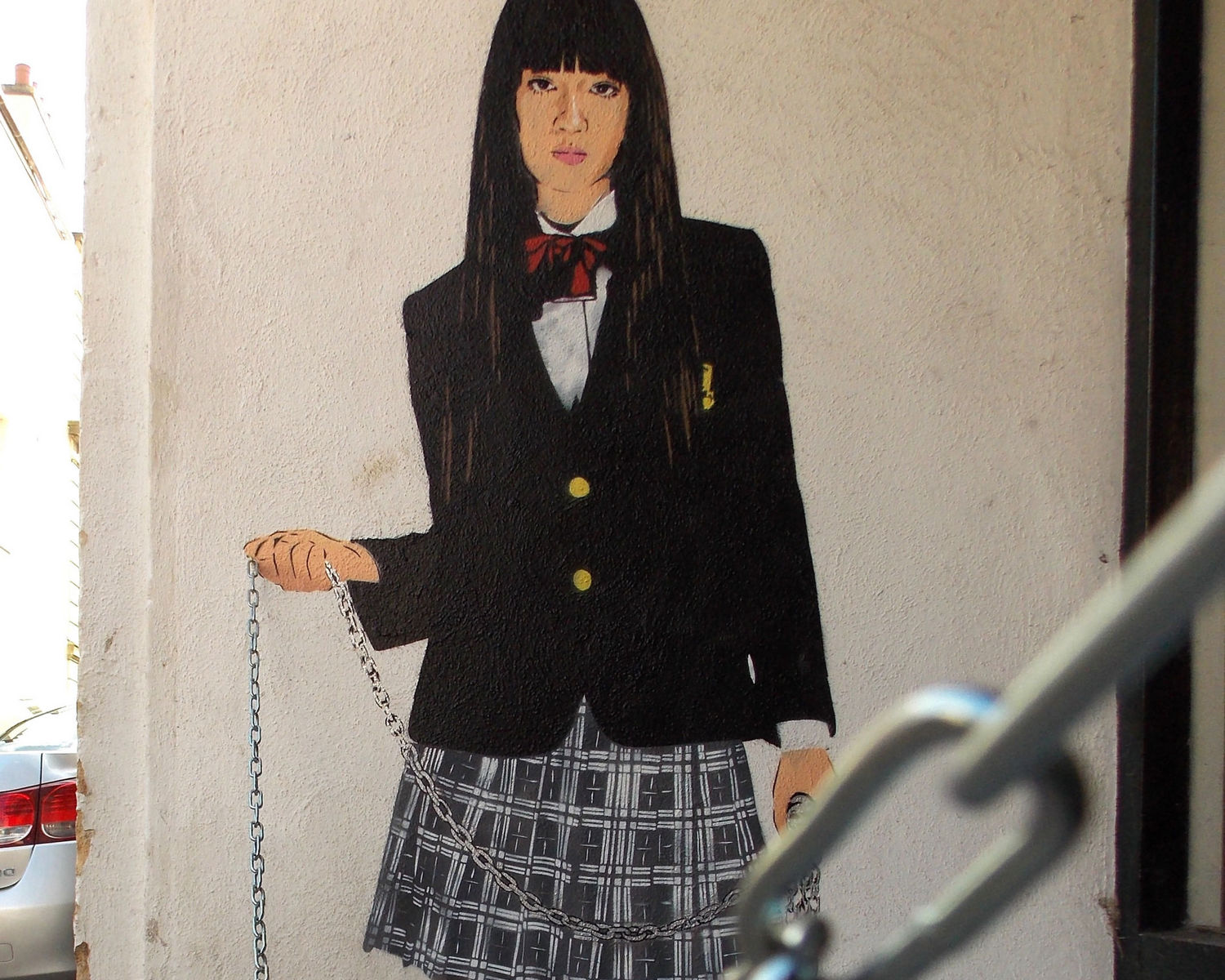

They greet us from house façades and walls, bring grey concrete columns to life, endow faceless electrical substations and construction fencing around building sites with unexpected aesthetic qualities and take us by surprise in unexpected locations. Street art is nonconformist, joyously experimental and, for many, is seen as the most lively and imaginative contemporary art form. Hardly anything embodies the topos of change in such myriad ways as street art. And in this sense, the street art exhibition “Magic City – the Art of the Streets”, which took place during the spring and summer of 2017 in Munich’s Olympiapark, declared: “Street art can transform grey walls into colour, make walls collapse, offer a promise of change, for a better future, shouting, whispering, provoking, stimulating new ideas or by simply bringing pleasure.” I couldn’t think of a better way of putting it.

Changing urban spaces

Street art adds visual highlights to the world’s metropolises, whether New York, Berlin, London, Melbourne or Buenos Aires. Even a lot of smaller cities like Marseille, Belfast, Rotterdam, Mannheim and Thessaloniki are seen as veritable street art hotspots – with these street artworks they have been given an aesthetic facelift or, as in Granada, have surprised us by revealing a new and, until now, unknown side.

The birthplace of street art was – where else? – New York where a huge graffiti boom was unleashed during the sixties and seventies. In the eighties, star artists like Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat created large-scale artworks on the façades of buildings. While the street art pioneers concentrated on walls and train carriages, artists today have extended the radius of their activity to encompass the whole city. With incredible 3D illusions, sculptures and miniature worlds, monumental murals and multi-media installations, they have conquered the whole urban space, and changed the cityscape with it. The trend of urban knitting is seeing lampposts, street signposts, bridge railings and tree trunks being decorated or completely covered with cheerful, brightly knitted accessories. And adbusting is the process of altering advertising hoardings and billboards by sticking new panels over them, or by subverting their original messages.

Street artists aim to surprise passers-by with their alterations to the cityscape. Unimaginative architecture, bins, electrical substations, gloomy subways, construction site panels – not only is the aesthetic aspect of the urban environment transformed through these imaginative, humorous or provocative works of art, but they are given a new content that makes people reflect and, according to the creator’s intention, amazes them, makes them laugh or think about the artist’s message. These everyday elements of street scenery are endowed with a quality that goes beyond their essential function and in this way the artist is consciously questioning contemporary city space.

A change in artistic perception

On the one hand, street art does away with the strict separation between everyday city life and its infrastructure and, on the other, the reception of art within a clearly demarcated zone. These often entertaining or politically motivated works can be encountered anywhere, but not in traditional art venues: museums. In this way, art is made accessible to everyone. It can be appreciated in a different way and encountered everywhere, by chance or literally in passing. The trepidation that some people have in visiting galleries is not a factor with this kind of art. Street art therefore reaches people of all ages, every social class, from different backgrounds and educations.

You can discover street art on the way to the office, school, out shopping or while waiting for a bus. In Hamburg’s city centre, for instance, artists have begun a small series of street art interventions: using chalk, they have divided the waiting areas of several bus stops into two, challenging the waiting passengers to choose one of the two areas, for instance, “I love animals” or “I love meat”. In this way street art can, for a moment, awaken people from their reverie or their daily routines, encouraging them to interact with the artwork and the message behind it. Food for thought “to-go”, so to speak. The idea of these Hamburg artists is to demonstrate that street art brings about change, but also is itself subject to this process of change and is not created for eternity. Street art is predominantly an art form for the moment, or for a limited timespan that cannot always be determined by the artists themselves. How a work of art changes and when it disappears will be decided by the city’s cleaning staff, wind and weather and sometimes also the demolition ball.

Changes in society

Artworks in a public space change our image of the city. But they can also demand change. Unlike in the case of classic graffiti, today’s artists are not interested in marking out their territory with so-called tags. Their works are rather statements about contemporary social and political subjects or content within the urban space. With his street art project “Splash and Burn”, the Malayan-based Lithuanian artist, Ernest “ZACH” Zacharevic, for instance, is protesting the destruction of the natural world. During the Arab Spring, Egyptian street artists transformed whole streets of grey, concrete Cairo into a colourful open-air gallery.

With their art, street artists, like graphic designer and art historian Bahia Shehab whose works can now be found in galleries in countries including Germany, China and Italy, wanted to lend support to the revolution and make a contribution to the democratic transformation. As in Cairo, everywhere else in the Arab world, whether in Tunis, Alexandria or Tripoli, walls and buildings have become canvases on which the street artists gave artistic and irresistible expression to their demands for reform. With her bright and colourful crochet work, the Polish-born, US-based Agata Oleksiak, alias Olek has been directing people’s attention to the world’s problems, whether pollution, human and women’s rights or Donald Trump, for over ten years now. In her works of art, cars, entire apartments and even living people disappear under her crocheting thread. She has also given the famous Wall Street bulls (see our cover) a crocheted coat with bright pink patches. Like Olek, street artists around the world are standing up to dictatorships, injustice, racism and sexism. The art of change – for a better world.

“Change” is also the topic we have devoted this edition of TWELVE to. And, as always, we don’t just want to communicate our chief topic through inspiring articles, but also exceptional visual design. For this reason, alongside Olek, we have invited other exciting street artists to open each of the twelve chapters of TWELVE with one of their artworks.